Student Strike, 2012: A Brief History

By anonymous

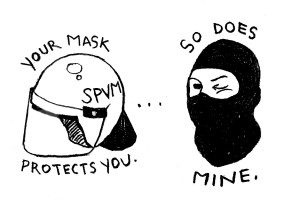

From February to September 2012, the longest student strike in the history of Quebec took place. Over the course of seven months, the city of Montreal was turned upside down by continuous demos, blockades of classes, street festivals, occupations, and acts of vandalism, sabotage, and economic disruption. A spirit of festivity wove through the months, as thousands were brought together in a joyful abandonment of student life. In an effort to crush the movement, the provincial Liberal government passed “Special Law” 78, imposing strict limitations on demonstrations near campuses, and suspending the winter semester at many universities and colleges that saw heavy strike action.

Quebec’s student movement is distinct from those elsewhere in North America. Influenced by the rise of student syndicalism in France that began during WWII, the idea of combative student organizing began brewing here in the early 1960s. The first general student strike took place in 1968, ending with the creation of UQÀM and the Université du Québec network of public universities, as well as a new system of financial aid.

From 1968 to 2012 there have been seven major strikes, along with a few duds. The student movement has grown, fluctuated, and evolved. Various federations formed and dissolved before yielding the current mix: FÉCQ and FÉUQ, the massive federations that favour reconciliation with the government, and ASSÉ, the syndicalist federation that favours combative mobilization as a means of advancing student goals and demands.

While the student culture at francophone universities and Cégeps has evolved with the student movement through the decades, anglophone campuses have largely remained outside of this culture of resistance. This began to change in the 2012 strike, with two occupations at McGill, and blocked classes and demos at both McGill and Concordia.

In mid-August, with a provincial election pending and the semester set to restart, most student associations voted to return to class, awaiting the elections for a revote. As the PQ came to power announcing a tuition freeze, this chapter in student mobilization came to a close. However, as Premier Marois announced the indexation of tuition fees (increasing at pace with inflation) this past February, grumbles of discontent began once again, alongside questions of how to move forward.

Social Strike?

Following the passage of law 78, people in popular neighbourhoods of Montreal began to go on their balconies and bang on pots to signal their opposition to this attack on the right to assembly. Modelled after a similar tactic in Pinochet’s Chile, this soon morphed into “casserole” demonstrations, where people of all different ages took to the streets to make a racket.

Out of this spontaneous mobilization came the formation of popular assemblies in many neighbourhoods, primarily with the aims of supporting the student strike and resisting the heightened repression of the Liberal government. All this came after calls for a “social strike” by various student assemblies, and discussions among student and non-student radicals of how to expand the struggle beyond students and youth. These discussions had been largely fruitless up until this point.

The summer progressed, and many neighbourhood assemblies turned their energies toward supporting students in blocking classes as the semester would begin once again in August. As the student strike came to an end, however, many of the assemblies fizzled out. Nevertheless, the memory of this moment remains as food for thought, given the inevitability of future student mobilizations.

The question of how to build meaningful links outside of existing student and radical milieus arose from these events. A culture of self-organization and direct action made the strike more than merely students blocking classes. These practices may be shared, understanding that we possess the means to pursue our own struggles without waiting for an ideal moment. As we communicate between diverse social networks and find common ground in spite of differing social positions, we may push the bounds of the student movement toward broader struggles for collective liberation.