Traces of Home: Reflections on The Queer Home Project

by Manvendra/Noor

@thequeerhomeproject

This project began in absence.

Growing up queer in India without the language to name my identity, I remember a void, a sense of not seeing myself anywhere, of not finding anything that resembled my experience of home or belonging. More than just a lack of representation in the visual and cultural landscape, it was also the absence of modes of relation, care, or familiarity. I think that’s where the initial spark for this work came from: a desire to build an archive of what is already visible, though fleeting, fragile, often unspoken and maybe even ephemeral (as contradictory as that may be with the notion of archive.)

Inspired by the late Cuban American performance studies scholar José Esteban Muñoz’s framing of queerness as something not yet here: an ideal, a horizon, The Queer Home Project is an attempt to build something toward that horizon. The on-going project, which started as part of my coursework at the Université de Montréal had the main motive of thinking about the idea of archive more than to capture or classify is to gather fragments: voices, texts, memories, images, rituals, that might together gesture toward the textures of queer home-making, especially for those for whom “home” is precarious, impermanent, or unsafe.

For many queer and trans people, particularly in the Global South, home is rarely a fixed place. It might be a feeling, like a kitchen on Sunday, or a moment of shared laughter in a WhatsApp group chat. A softly lit room in which you are not asked to explain yourself.

This project tries to hold space for that kind of remembering.

I chose Instagram as the medium, despite its contradictions. Platform capitalism is a surveillance trap, but it is also where queer communities in India find lifelines during moments of isolation. I remember how, during COVID-19, Instagram became a mutual aid network: people crowdsourcing oxygen cylinders, medications, funds, groceries and urgent care. It also became a queer commons of sorts where art, grief, support, and solidarity circulated in stories and posts. I wanted to tap into that possibility. The form itself, temporary (or not), visual, interactive felt aligned with the nature of the archive I was trying to build.

I call it a resistant archive. One that doesn’t try to fix meaning. It doesn’t attempt to define what queer home is, but rather listens to how it is imagined, lost, built, and rebuilt. The idea of the “ephemeral as evidence”, coined by Muñoz, became foundational to the project: these fragments may not be considered legitimate “proof,” but they’re real, they circulate, and they matter. They may not always be facts, but they are truths. Felt truths.

I collected submissions through a google form in English, French, and Hindi for the resistant archive/queer home project. People were invited to share anonymously if they wished. The archive became a conversation, one mediated, but not authored by me. I became a curator, participant, researcher, and friend, all at once. These roles blurred, and that blurriness became part of the methodology.

Several submissions came from people that I knew. I hesitated. Was this too personal? Was it rigorous enough? But in the end, the stories themselves gave the project its shape and assuaged my ethics.

A few themes emerged: the quiet grief of not finding oneself in any known blueprint of belonging. The joy of discovering home in the most unexpected places, a song, a balcony, a memory of eating oranges with someone who made you feel seen. The tenderness of a chosen family meal. The pain of having to leave a home that was never really yours to begin with. The relief of finally being able to sleep through the night.

One person shared that their idea of home lived in a group chat with two queer friends, one of whom had passed away. That story remains with me. The way a digital space, mundane and fleeting, could become a sanctuary. A site of remembrance. A shadow archive of queer love and loss.

The contributions came from both India and Canada. Some were multilingual. Some never named gender or sexuality explicitly, but queerness was everywhere. It was in the way people described longing, resistance, memory, care, and survival. Gender was in the details: in the ways bodies moved through space, hidden under tables, held in gaze or avoidance, welcomed or denied. Often, these stories reminded me of my own. The pain of not fitting in. The deep, quiet affirmation of finding someone who gets it.

As someone now living between two geographies, I also began to notice the transnational echoes: how the two contexts had different ways of shaping expressions of queer home-making, about holding space for multiple archives to speak to each other.

What the archive leaves out is also important to consider: some stories are too tender, too painful, too un-formed to share. Some exist only through gestures, in silence. The contradiction of archiving is that it always misses something and perhaps, in queer contexts especially, that absence becomes part of the story.

This project reminded me that care can be a form of research. Asking someone “what does home mean to you?” is both a methodological inquiry and an attempt at relating. It opens the possibility of remembering and imagining home, otherwise. Not as a structure we enter, but as a space we make and remake, in language, in kinship, in ritual, in breath.

The attempt is not to make a grand archive. It’s small, partial, and messy. It refuses closure, poignantly. It doesn’t claim to define. It tries, instead, to hold. To witness. To offer a soft place for stories that might otherwise be lost, or never told at all. In that speculation of what it was, lies in the possibility of what it can be.

Speaking directly to an academic milieu, maybe these stories aren’t illustrations of theory. Maybe they are, themselves, theory.

“ Home is where I felt like a bird who can fly high.”

Home is where I felt like a bird who can fly high.”

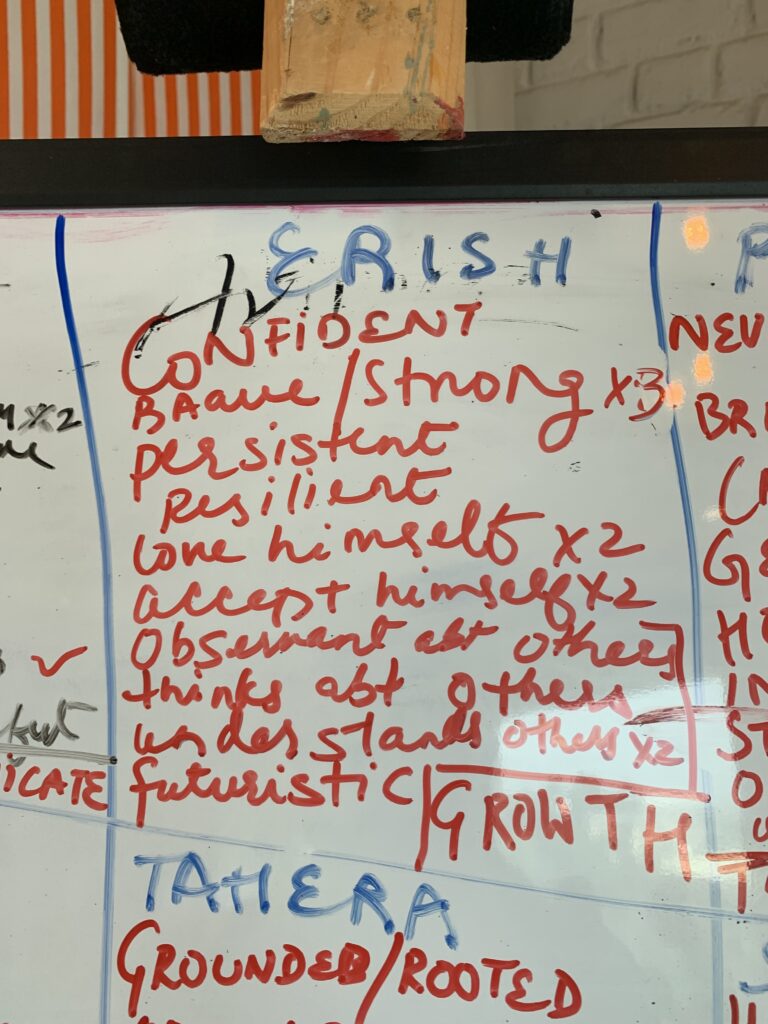

— Erish, 24, New Delhi

“A place [home] that hugs you back when you need it.”

— S, 23, Montreal

“It’s not the house, it’s the entire city [that feels like home].”

— Anonymous, 18, New Delhi